Hessie : la restauration du Temps Perdu

The exhibition

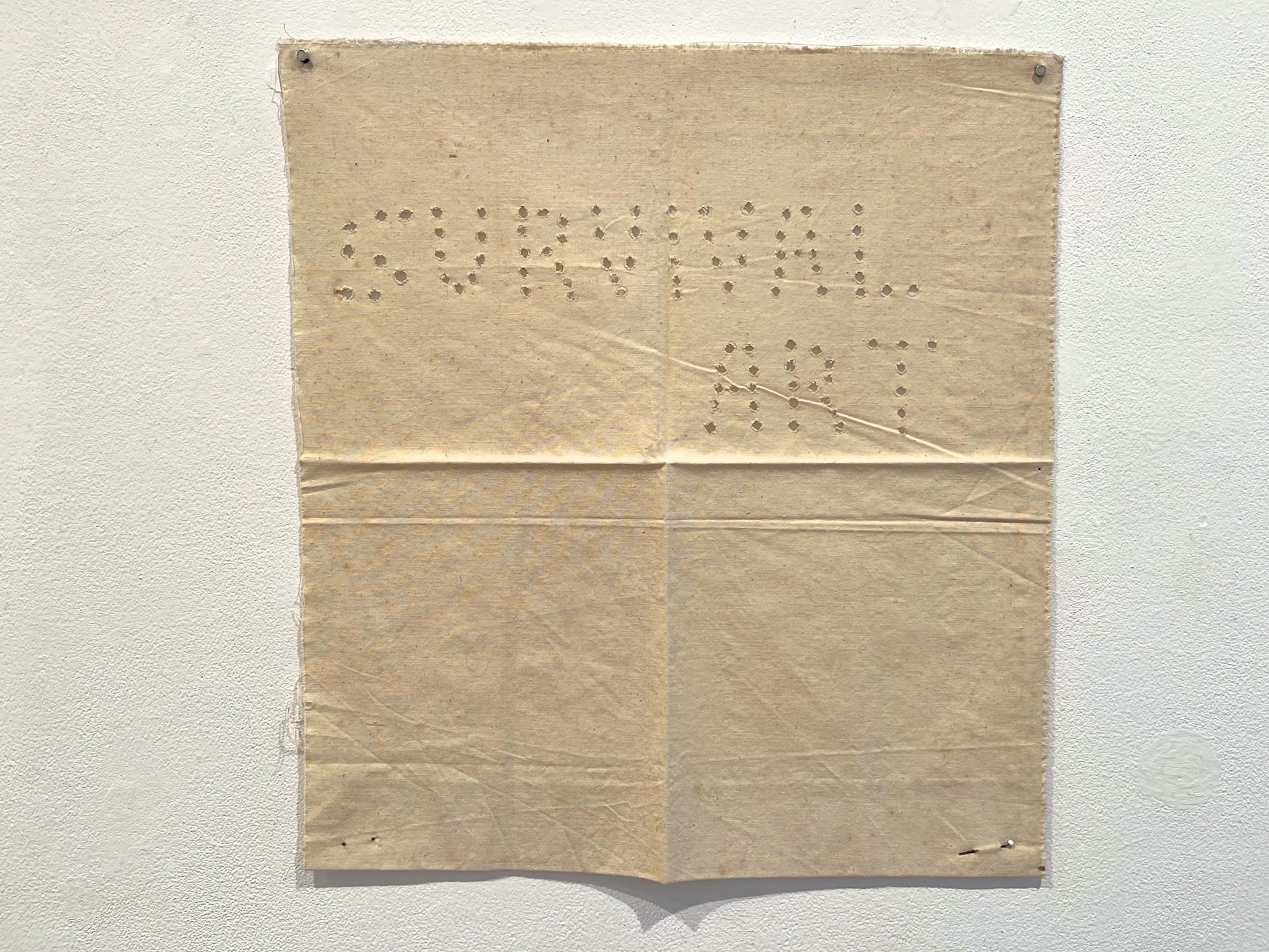

“Everything in survival is reduced to very simple proportions.[1]” In 1975, Hessie forged the term “Survival art” to define a practice that was both minimalist and subversive. In the economy of materials, forms, colors and motifs, she found an artistic language of profound intensity. Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre's “Temps Perdu” exhibition plunges into the heart of this incisive creation. The title echoes one of her iconic works, “Temps Perdu” (1972), and highlights a series of “perforations on paper”. Carmen Lydia Iguartua Pellot, whose real name is Carmen Lydia Iguartua Pellot, refuses to be called an artist. She creates “non-tableaux” [2], in which needle and thread become the tools for questioning the domestic and the role assigned to women. A freedom of tone and expression that runs through all her art, reinventing embroidery as a gesture of resistance.

Involved in the feminist movement since 1968, she defends her rights and takes a stand through works such as “Oui/Non” (1975), in which an adverbial phrase is embroidered in red thread on cotton fabric. The canvas is the embodiment of a previously thought-out artistic act. For this piece, she first photographed one of her multi-holed works [3] before perforating the raw paper with the inscription Oui/Non, accompanied by the subtitle “le droit de vote de la femme” (“women's right to vote”). The result is a composition that stands out as an emblem of social and political commitment. A work that reminds us, with force and simplicity, of the importance of consent.

Long confined to the domestic sphere, the embroidery language, perceived as feminine, is gradually gaining recognition in the artistic field. A shadowy artist, Hessie appropriates this ancestral heritage and twists it to achieve feminine empowerment. The repetition of gesture and motif lends her work a meticulous precision, in which symmetry plays an essential role. In “Untitled” (1976), she reveals the complexity of marking letters, printed on fabric using a typewriter. Writing thus occupies a privileged place in her creations. Faced with oblivion and erasure, Hessie imposes her own timeless language, leaving behind veritable traces of life.

The formula “restorer of lost time” provides a better understanding of her approach, where artistic creation and commitment merge. Her art, as Arnaud Lefebvre points out, is to be considered “from the point of view of loss and lack” [4]. These absences shape her practice, to the extent that she does not always ensure their conservation. The term “restorer” finely links the recovery of so-called “poor” materials - wire mesh, thread, vegetable netting, etc. - with her visceral desire to reinvent her time. In this way, Hessie explores the ambiguity between the loss of material and the omnipresence of a unique language that permeates each of her creations.

Hessie, Temps perdu, partie I, Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre, Paris until April 19 2025

Agathe Fumey

[1] Text included in the Hessie archives recently donated by his family to the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

[2] Panico Léo, Antidote, “How did visual artist Hessie invent ‘Survival Art’?”, Survival Spring-Summer 2019.

[3] Photograph by Trous (No.Inv.206).

[4] Lefebvre Arnaud, “Temps Perdu, Part I, Hessie”, Press Kit, 2025.

Involved in the feminist movement since 1968, she defends her rights and takes a stand through works such as “Oui/Non” (1975), in which an adverbial phrase is embroidered in red thread on cotton fabric. The canvas is the embodiment of a previously thought-out artistic act. For this piece, she first photographed one of her multi-holed works [3] before perforating the raw paper with the inscription Oui/Non, accompanied by the subtitle “le droit de vote de la femme” (“women's right to vote”). The result is a composition that stands out as an emblem of social and political commitment. A work that reminds us, with force and simplicity, of the importance of consent.

Long confined to the domestic sphere, the embroidery language, perceived as feminine, is gradually gaining recognition in the artistic field. A shadowy artist, Hessie appropriates this ancestral heritage and twists it to achieve feminine empowerment. The repetition of gesture and motif lends her work a meticulous precision, in which symmetry plays an essential role. In “Untitled” (1976), she reveals the complexity of marking letters, printed on fabric using a typewriter. Writing thus occupies a privileged place in her creations. Faced with oblivion and erasure, Hessie imposes her own timeless language, leaving behind veritable traces of life.

The formula “restorer of lost time” provides a better understanding of her approach, where artistic creation and commitment merge. Her art, as Arnaud Lefebvre points out, is to be considered “from the point of view of loss and lack” [4]. These absences shape her practice, to the extent that she does not always ensure their conservation. The term “restorer” finely links the recovery of so-called “poor” materials - wire mesh, thread, vegetable netting, etc. - with her visceral desire to reinvent her time. In this way, Hessie explores the ambiguity between the loss of material and the omnipresence of a unique language that permeates each of her creations.

Hessie, Temps perdu, partie I, Galerie Arnaud Lefebvre, Paris until April 19 2025

Agathe Fumey

[1] Text included in the Hessie archives recently donated by his family to the Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

[2] Panico Léo, Antidote, “How did visual artist Hessie invent ‘Survival Art’?”, Survival Spring-Summer 2019.

[3] Photograph by Trous (No.Inv.206).

[4] Lefebvre Arnaud, “Temps Perdu, Part I, Hessie”, Press Kit, 2025.

When

04/03/2025 - 31/05/2025

.jpg)